Synopsis

Recognised breeds have played valuable roles in the development of beef industries world-wide, based on combinations maintaining valuable characteristics and making genetic change. This history has depended on combining skills of animal observation and understanding market needs, with use of technology and marketing and communications. As pressures on land use and from competing food sources rise, and ‘genetics’ morphs into ‘genomics’, the pressure to utilise breeds’ genetic resources is going to become more acute. In parallel, the very basis of breed organisation will be challenged, as the overriding importance of sound performance data becomes clearer. The challenge of how to collect, share and use the most appropriate data to underpin genomic selection is being tackled in a range of ways in different countries. This paper focusses on the core principles of genomic selection for beef breeding, and explores strategies for the data to information process which is central to survival in the genomics era.

Introduction

The beef industries of most developed countries depend on a range of breeds and crossing systems, with a corresponding variation in how genetic improvement is delivered. The role of breeds (breed societies, associations) in genetic improvement also varies.

In this paper I will outline some challenges and opportunities facing breeds, and in particular, explore some key strategic choices generated by the advent of genomic technologies.

Firstly, let me make clear how I think about breeds. A breed is:

- A population or gene pool of animals, often originally deriving from a particular region.

- The animals in that population typically have distinctive and relatively uniform appearance (size, colour markings, horns etc), which to some extent acts as a marketing device and is frequently managed as such.

- Deriving from the appearance in the broad sense, the population will have characteristic performance for various traits (size, growth rate, carcase traits etc), which will differ from other breeds to varying extents for various traits.

- And ‘it’ is an organisation of people, working together in some way to promote their interests

Historically, what the cattle did (in terms of their typical performance) determined the role of the breed, its market share and distribution.

Increasingly, it is what the people do that determines the fate of a breed, and I will argue that this will become even more the case in the genomics era.

I take some important things as givens:

- Selection is possible for all traits impacting profit.

- Recording (and genetic analysis) is essential for genetic improvement.

- Genetic merit impacts market share – it’s critical to commercially meaningful survival.

The business of breeds

If we think of a breed society or association as a business, how does it operate?

In simple terms, members invest time and money in recording, selection and marketing, potentially making some change to the performance characteristics of the animals, and capture some share of total value chain margins via sales of bulls, cows, semen etc.

In Australia, the share of total on-farm income that accrues to bull-breeding is around 6–10%: the average price of bulls is about 6–10% of total lifetime progeny value per bull.

We have limited data on breeders’ operating margins, but in broad terms they:

- Are strongly influenced by current prices for slaughter stock.

- They are not markedly different from margins achieved in commercial production, but carry the additional risk of investments in recording and evaluation, infrastructure and marketing.

In Australia, the breed societies operate as not-for-profits, aiming (to varying extents) to invest any surplus in some combination of R&D and marketing.

From a genetic improvement perspective, there is a simple equation that strips the business down to fundamentals (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Animal breeding and production as a ‘data to information’ business.

The overall aim is to maximise returns from whatever investments are made – this applies whether we are talking about single vertically integrated organisations such as pig or poultry companies, or breeds with many members supplying bulls to larger numbers of commercial producers.

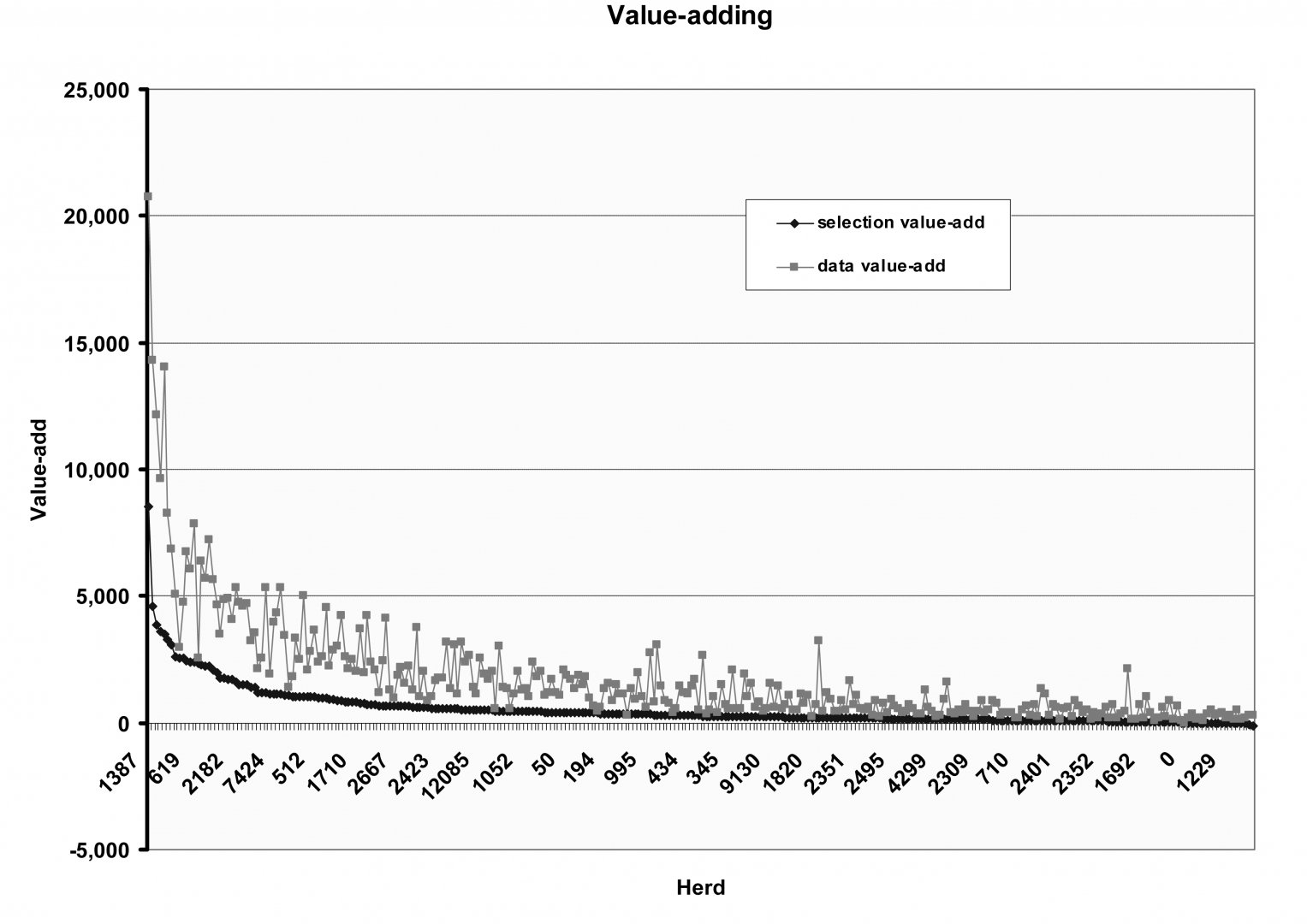

What makes this model challenging for breed societies is that the overall outcomes reflect the decisions of many individual members, and those decisions vary – individual breeders invest different amounts in recording, they likely vary in the ways they make selection decisions, and they make genetic progress at different rates and in different directions (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Variation in value-add between herds within a breed.

This variation is unusual if we think of breeds as brands: it is as if the features of a car depended to some extent on which distributor you got it from. I’ll return to this point.

The other aspect of the breeding business which is very different from most branded products or services is that the breeders within a breed ‘cocreate’ the value. This is because the work that individual breeders do – the recording and selection – helps both them as individuals but also the other breeders. The data collected on individual animals contributes to the evaluation of other animals in the breed, and breeders exchange (usually by buying and selling) genetic material with each other.

In economic terms, this makes a breed society a club – an organisation in which members contribute to generate or something together which they could not generate or create as individuals. A golf club is an example: members share the costs of owning a course, paying a professional, having a members’ bar and so on.

A breeding ‘club’ takes this one step further through the direct injections of pedigree and performance recording data and of genetic material, which together generate the average and variation in genetic merit for all the various traits. Adding to the ways in which breed societies are unusual business models is that to varying extents the members compete with each other in bull selling.

A jargon term for this mix of cooperation and competition is ‘co-opetition’ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coopetition).

These interesting aspects of breed societies represent a challenge and an opportunity. The variation in behaviour of members can be seen as an inefficiency, and the typically imperfect flow of signals for genetic improvement encourages more investment in marketing than in genetic improvement – which is ultimately the source of success for the breed.

To many, these challenges result in breed societies being seen as a frustration, and the strategy inherent in much implementation of genetic improvement technology has been to remove the frustrations – by establishing single enterprise businesses, such as pig breeding companies. In these ultimate decisions about investment in recording and selection are made at a single point, even when multiple individuals contribute to the decision-making.

My point here is not to suggest that breed societies should aim to be more like vertically integrated companies, although that would be a legitimate strategic choice. It is to note the way in which decision making about investment and selection are distributed, and vary, among members, and that this distributed investment is loosely coordinated by a combination of the society’s rules, and by the market.

I am not suggesting that breed societies are inherently a bad (or good) thing: they are a form of organisation that has emerged quite naturally, and have potential to be effective or not. Perhaps their most significant feature is the variation amongst their members: effectively utilised this variation is the source of evolution, just as variation in genetic makeup is the source of evolutionary change, and of genetic improvement in livestock.

I am not focussing so much on the organisational effectiveness, as on examining how the ways breed societies work might be impacted by implementation of genomic methods.

Genomic selection – what’s different?

The starting point here is the key technical features of genetic improvement in the pre-genomics era:

- phenotype + pedigree = EBV

- accuracy (information) disperses in proportion to animals’ relatedness

- accuracy (information) is spread primarily via movement of animals

- risk, which is mainly about investment in recording, is spread widely across the members of a breed society

- and we typically see characteristic patterns of amount of recording and of rate of genetic progress

A core aspect of this era is that effectively, to determine the genetic merit of an animal, you have to record something about that animal: its pedigree and some aspect(s) of performance.

What about genomics? Implementation of genomic methods is primarily about genomic selection. The basic features of genomic selection can be shown summarised:

- Reference population. This is all animals with a genotype and some measure of performance, which can include an EBV based on their progeny or other relatives’ performance

- Genetic analysis that incorporates pedigree, genotype and performance information, and which can therefore calculate EBVs for animals that only have genotypes. The method of choice here is multitrait single step, such as is now implemented in BREEDPLAN

Once these two items are in place, animals outside the reference population can be genotyped and obtain useful EBVs.

The game-changing (‘disruptive’) aspect of this model is the establishment and utilisation of a reference population:

- the reference population is animals with phenotypes (records) and genotypes.

- the reference population can be a discrete herd recorded for some defined set of traits, it can be animals in or from a range of herds recorded for a variety of sets of traits, or a combination of the two.

- anyone can then draw on the reference data simply by genotyping an animal and including the genotype in a genetic evaluation.

Note that in principle some core of animals with identified pedigree has always existed – the difference is that now, one can utilise information from the reference without needing to know pedigree. (This points to a very important fundamental – it is now possible to determine pedigree, and much else about animals, without maintaining a herd book).

The core of this change is that we can decouple evaluation (determining ananimal’s genetic merit) from recording. To stress the point, previously, if an individual member of a breed society wanted to determine the genetic merit of their animals, they needed to invest in recording those animals.

Now, they can achieve this by pulling tail hairs and submitting genotypes to the breed genetic evaluation. One immediately obvious consequence of that fact is the potential for free-riding, depending on who invests in the reference and on what terms others can access it.

This potential for free-riding is just one aspect of how genomics challenges a breed society business model. I will briefly outline the aspects, with suggested approaches in each case.

Before doing that, it is important to stress that genomics offers real opportunity for significantly faster and more valuable genetic progress. We are starting to see the practical evidence for that in beef breeds in Australia. The increases in accuracy of predicting progeny performance are substantial – up to 20% depending on breed and trait, meaning that stud breeders can select young bulls and heifers, with more accuracy for more traits, meaning faster and more valuable genetic progress is possible.

Strategy for breeding businesses

Strategy for any breeding business is ultimately defined by the answers to two questions which both interact and at the same time involve specific challenges for multi-member organisations.

Those questions are:

- what to breed for?

- what to record?

I’ll examine each one, with particular focus on how they apply in the case of breed societies. First, a comment on how these two questions have tended to be answered in beef breeding, and how this is changing in Australia.

Traditionally, breeders seem to have selected for the things that are relatively easy to record. Growth rate, or weight, is the best example, so we have seen selection for increased growth rate and size through life in most breeds in most countries during the last 20+ years. A minority of breeders have carefully recorded birth weight and adult cow weight, and to some extent (increasingly in the last 10–15 years) have selected to bend the growth curve – holding birth weight, going for rapid early growth, then putting a cap on adult weight. This pattern is now a central feature of the $Indexes being developed by most breeds using BREEDPLAN in Australia.

Simply selecting for what is easy to record is not sensible.

What to breed for – the breeding objective:

All breeds have typical performance for a range of traits that affect income and/or cost through the value chain. The breeding objective is a formal statement of how much the breed wishes to change performance for one or more of those traits. Geneticists tackle this by working out the impact in financial terms, and using those ‘relative economic values’ (revs) to weight different trait EBVs in a selection index.

The first key point here is that the breeding objective ultimately defines the direction of genetic improvement – what traits will be changed by how much.

Ideally, a breed will have a welldefined breeding objective, and that will at least inform individual breeders’ selection choices.

In the genomics era, the breeding objective becomes significantly more critical, because it explicitly tells us the value of different trait records which should shape investment in the reference (the breeding objective has always been important, even if not often formally developed and widely utilised). For example, a trait with very high rev is much more valuable to record than one with a low rev. This feeds directly into decisions about investment in the reference population.

What to invest in – what to record:

The second key point is all about what to record, or more precisely, what to record in the reference. It is the size and trait coverage of the reference population that determines what value breeders and others can extract through genomics.

Ideally, in the reference population, the breed will get sufficient numbers of trait records for all the traits in the breeding objective, or traits that are closely genetically related to those, as possible. Sufficient numbers is not a fixed thing, but breeds should aim for 250–1,000 new animals recorded and genotyped per year – higher numbers simply generates greater genomic accuracy.

This clearly leads to asking the question ‘how does the breed fund the reference?’ There are several points that can be made here:

- If this is left to individual breeders, how can the breed guarantee that it will get enough records for all the important traits?

- If the breed is investing in specific recording activities or herds, either alone or in partnership with (for example) R&D agencies, how to recoup the cost? Even if there is no charge applied, the funds will have had to come from somewhere.

- If the breed has a mix of reference recording, through breeders’ individual efforts in combination with some form of ‘central’ recording, how to recoup the costs, and provide some recompense to the individual breeders?

There may not be any one definitive answer to these questions, but I believe that some principles can be identified:

- If everything is left to individual breeders, their propensity to invest in trait recording, in particular for hard-to-measure traits, will be powerfully affected by the recording cost and the likelihood of getting an adequate return, likely via bull sales. If there is uncertainty around those returns, there will be underinvestment in trait recording, and the breed’s capacity to exploit genomic selection will be compromised.

This implies that some form of payment for records must be considered. That leads to the questions of:

- How much to pay for trait records?

- How to generate funds to pay for trait records?

- What form should the payment take?

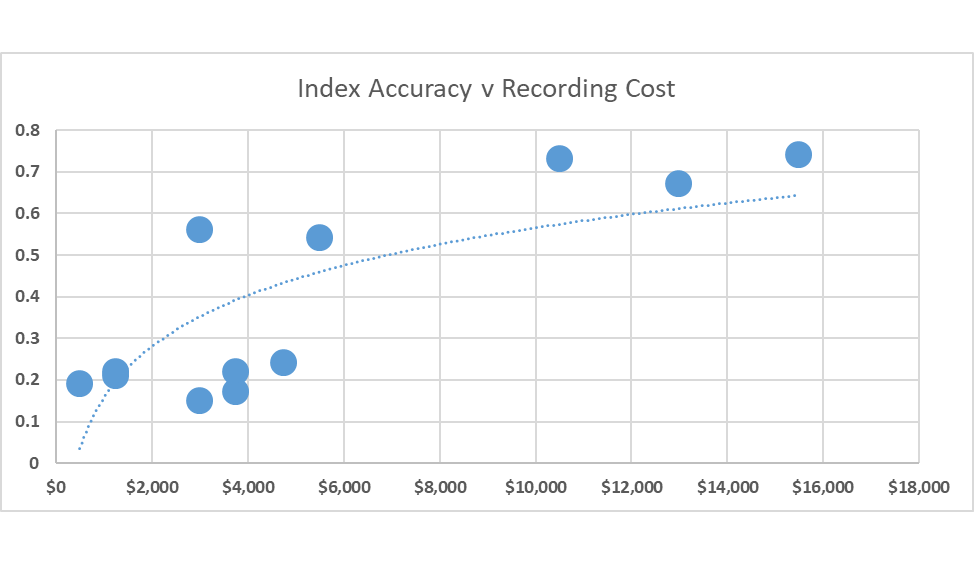

- How much to pay? I believe that solving this question depends on the relative economic value of the trait, coupled with any range in anticipated recording cost. For any combination of trait records, we can calculate the impact on index accuracy, and evaluate that against the recording cost (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Example Accuracy v Recording cost chart.

Any breed can construct its own version of this chart, each time new investment decisions must be made, and use it to prioritise investments.

An extension of this principle is that the data recorded by each member of the breed and contributed to the reference can be assessed for the value of its contribution. This leads to considering whether to actually pay, or provide something in return, for that contribution. Currently, as discussed above all breeds effectively rely on bull (or semen) sales covering those costs, and/or contributions from research funds of some sort. Even if both these options still apply, consideration does need to be given to recompense for the breeders who record performance, otherwise the overall recording effort will almost inevitably decline, and with it, the value of the reference population and the potential to benefit from genomics.

- How to generate funds to pay for trait records? In principle, this is straightforward: simply impose a levy on genotypes processed within the genetic analysis – the total cost of records divided by the anticipated number of genotypes.

- In practice, the breed may wish to differentiate between different uses of reference data. To explain, a bull breeder will obtain more value from a genotype, if it leads to sale of a bull, than a commercial producer.

It would be possible to vary the levy in proportion to the anticipated number of expressions of the genes of the genotyped animal.

- How to pay? The easy answer to this is ‘via cash’. The problem with this easy answer is that it implies that breed societies become a form of bank, holding reserves, receiving payments for services (which they do now), and making to some members.

- In practice it may be simpler to provide some form of credit for breeders or other individuals who contribute data to the reference – making services available to them at reduced rates. The US dairy employs this model currently.

The genomics challenge to all breed societies

In the pre-genomics era, most breed societies largely left genetic improvement to chance and the market.

This generated considerable underperformance (lower rate of genetic improvement than possible) and wide variation in that rate within and between breeds. Together, this generated massive opportunity costs for everyone in the value chain (and the communities that depend on them).

Genomic selection will force breeds to focus on two core strategic questions – what to breed for, and how to fund reference populations.

There are simple metrics available that can inform the decisions needed, including metrics relating to the variation in contributions made by individual members.

Furthermore, the scope to redefine membership is a significant opportunity. Commercial producers, processors and even retailers and consumers can be seen as partners in data capture and therefore potentially new classes of members.

Large breeds will potentially find these challenges easier to overcome, basically because their costs of reference can be spread over more commercial expressions, especially with wide use of AI.

However, the basic ratios commercial expressions: stud numbers are roughly constant, so there is scope for smaller breeds to close the gap.

In this context, international collaboration is potentially more valuable for smaller breeds, because there are diminishing returns to scale in the accuracy of the reference population. Breeds should explore sharing data between countries, and enhance the effectiveness of this by coordinated use of elite, genotyped young sires across countries.

Central to all these challenges is the question ‘how to pay for all this’, on top of the costs of genetic evaluation and other roles of breed societies. (One response is to simply use the performance data and (genomic) pedigrees – why have breed societies at all?)

Finally, breeds should certainly explore scope for long-term funding relationships with industry and/or government organisations. Beef cattle breeding is more affected by market failures than the vertically integrated industries, co-funding of reference data offers a very efficient way of reducing the opportunity costs of those failures.

The core of my message is that ‘genomics’ provides the opportunity, and the very powerful challenge, to re-think how breed societies work as organisations. The metrics that are readily available around genomic selection can be used to re-shape how breed societies work: what are their rules around use of the key information resource, how are costs distributed? The breeds that emerge from the genomics era intact and viable will have inevitably had to trial new ways of doing things, but in finding practical, equitable and efficient ways of generating and using information, they will have a much stronger foundation for sustained viability than previously.