Summary

Modern farming methods claim to offer an affordable, safe and diverse food supply to all. However, systems that confine animals or manage them in environments perceived as ‘unnatural’ can provoke negative responses from media, welfare groups and the public. This study set out to understand whether preferences within the UK vary for a number of attributes relating to milk and the way dairy cows are managed, and what might explain these differences. A survey asked 2,054 UK citizens to rank a set of 17 attributes relating to milk and aspects of cow management. Analysis showed significant differences in priorities and ranking order of the attributes according to a range of factors such as age, gender, education, dietary choices, knowledge, experiences and value system. Further analysis revealed six ‘segments’, each of which prioritised different attributes and had different socio-demographic backgrounds and attitudes.

Introduction

In UK dairy farming, current estimates are that 90% or more of the UK’s dairy cows access pasture in any one year (calculated from March et al., 2014). However, there are many reasons for housing cows longer and bringing feed to them rather than have them harvest it themselves through grazing. For example, a lack or surplus of rainfall in an area and avoiding long walking distances to pasture as herds grow or landbase shrinks (Van den Polvan Dasselaar et al., 2014).

While any impact on milk quality from the way the cow is managed is of direct concern to a consumer of dairy products, other aspects related to a perceived intensification of milk production often hold interest for wider citizens. Larger scale operations and housing animals yearround are popularly perceived to have negative impacts on the environment, rural communities, the viability of other dairy farms, cow health and welfare, and potentially the quality of milk (Miele, 2010; Cardoso et al., 2016).

While these and similar views emerge frequently in research, it is not clear how widespread or similar these attitudes are within the UK population, and what knowledge or perception they are based on. Understanding these preferences for milk and cow management practices, and how they vary among different groups, may help the dairy farming industry to modify both housed and grazing farming systems to bring both sides of the debate closer to a consensus, to change the way it communicates modern dairy farming systems, or even to target milk produced in different ways at certain consumer groups.

Methods

An online survey we ran through a consumer marketing panel set out to ask 2,000 people from across the UK to rank a set of 17 attributes of a cow’s environment and management related to space, commodification, behavioural enrichment, naturalness, access to both grazing and/or the outdoors, and health and welfare alongside other added-value features of milk as a product.

Best worst scaling (BWS) methodology was used with the aim of achieving an accurate, scaled ranking of the relative importance of the different attributes. The exercise presented the 17 attributes an equal number of times in 12 different sets of five, with respondents asked to select the ‘most’ (best) and ‘least’ (worst) important characteristics to them in each test when first presented with the following question:

‘You are in a grocery shop, walking through the aisle for milk, dairy and plant-based alternatives. More information than usual has been provided about the different types of cows’ milk on display. This has been supplied by a trusted food assurance scheme. Irrespective of whether you are buying any milk or not on this occasion, you have time to spare, so you read the information provided. You will now see a series of questions. Each includes five pieces of information about the cows’ milk on display. Which feature is the MOST important and LEAST important TO YOU in each set of five, if price is not an issue? There are 12 questions in total ’.

The aim was to examine the scaled rankings in relation to a range of different factors that might explain people’s preferences and trade-offs. In addition to questions about gender, the region the participant lived in, their age, educational background, income, ethnicity and family, they were also asked about their attitudes and beliefs towards dairy cow welfare, experience, knowledge of dairy farming and values.

Results

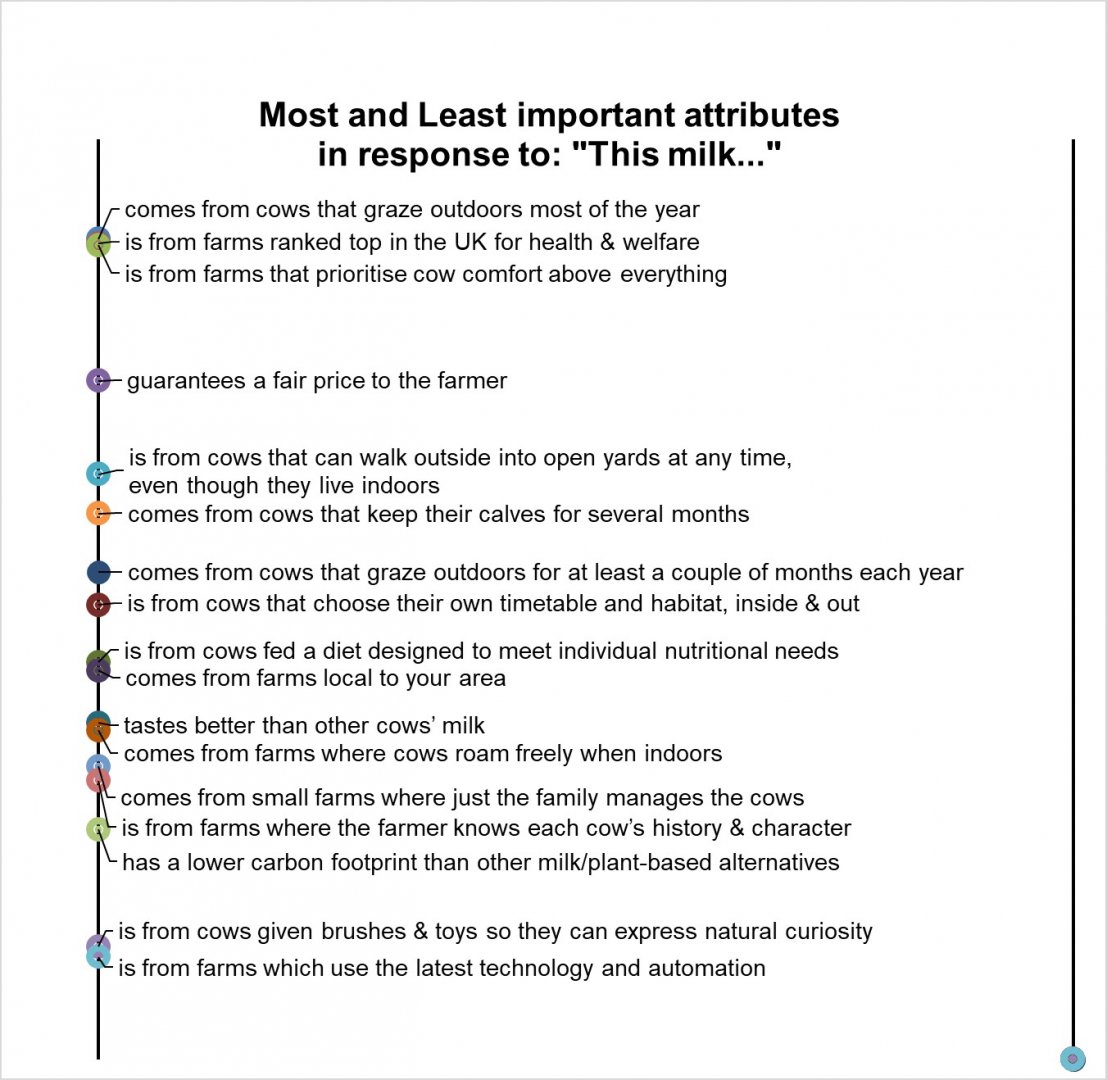

2,054 completed survey responses were received over the period of a week. ‘Grazing most of the year’ emerged as the most important attribute (see Figure 1), which was not unexpected, but this did not score significantly differently to either of the attributes relating to ‘health and welfare’ or ‘cow comfort’. These three attributes were most important overall, with the lowest-scoring of this trio, ‘cow comfort’, proving significantly more important than the next nearest attribute, ‘fair price paid to farmers’.

Figure 1: Mean rescaled rankings for each attribute across whole sample (n=2,054)

Variations in ranking were also examined according to a number of other factors such as gender, dietary preferences, types of milk consumed, the urban or rural nature of where the respondent has lived, experience of keeping animals and values.

There was a significant difference between the mean scores awarded by men and by women for the ‘grazing most of the year’, ‘health and welfare’ and ‘cow comfort’ attributes, with the ranking reversed to be ‘grazing’, ‘health and welfare’ then ‘cow comfort’ in decreasing importance for men, and ‘cow comfort’, ‘health and welfare’ and ‘grazing’ in decreasing importance for women. Other noticeable differences included women scoring ‘calves staying with cows for several months’, ‘cows accessing open yards even though they live inside’ and ‘cows choose their own habitat and timetable’ significantly higher than men; and men scoring ‘milk tastes better’ and ‘latest technology’ significantly higher than women.

As the number of omnivores in the sample was very large (n=1,718), the rankings from this subset broadly mirrored the sample as a whole. However, those on a restricted diet of some kind – including vegetarians, vegans and dairy-free – prized ‘cow comfort’ highest, with their scores for ‘calves staying with cows for several months’ and ‘cows choose their own habitat and timetable’ also significantly higher than those provided by omnivores. Those consuming plant-based rather than cows’ milk, although small in number (n=122), also prized ‘cow comfort’ very highly.

Further analysis to search for groups which ranked the attributes similarly identified six ‘segments’, each of which showed significant differences in prioritisation for most of the attributes. The segments were all of a similar size – between 15% and 20% of the total sample.

• The first group prioritised health and welfare and cow comfort, but was very altruistic and also wanted the farmer to get a fair price for milk.

• The second wanted grazing and outside access for cows, but was the most urban.

• The third preferred the taste of milk above other attributes and had those most focused on achievement.

• The fourth was focused on supporting farmers and local milk, and was the most rural.

• The fifth was all about cow comfort and choice, and cows staying with their calves for several months; most of the vegan and vegetarian participants, and those who consume plant-based milk were in this group.

• The sixth was an unusual group; like the first, they prioritised health and welfare but only just, with little difference in scores between all attributes. This group was very urban, the youngest, and had the lowest knowledge of dairy farming but scored themselves the highest.

Discussion and conclusion

This study raises questions as to what citizens, and consumers, actually value in the way a cow is managed and in the milk she produces, and what they associate with welfare and a better life for the cow. Literature suggests that consumers and citizens broadly view access to pasture or grazing as a proxy for good welfare, in that it supports a wide range of behavioural expressions for the cow, provides a ‘natural’ diet and – whether through impressions formed at a young age or as adults – is intuitively where cows belong. However, to also highly rank ‘farms that prioritise the comfort of their cows above everything’ and ‘farms ranked top in the UK for health and welfare’ suggests some devolvement of responsibility for cow welfare and wellbeing to farmers, because these descriptions contain no details of what actually happens on the farm, but instead specify the outcome.

Of further interest is the far broader range of priorities expressed by subsets of the sample than themeans of the whole suggests. When comparing to demographic,

knowledge, experiential and value system factors, the same top three priorities emerge time and time again, but with differences in the top preference. However, the six underlying groups that emerge demonstrate even more variation in preferences, with each class expressing a different ‘top’ priority such as taste of milk, cow comfort, health and welfare or a fair price paid to farmers. This suggests that where these groups have also identified grazing as a moderate preference, this could be for a variety of different reasons relating to other benefits grazing might deliver such as naturalness, better tasting milk and so on.

The results of this study suggest there is significantly more variation in preferences between different citizens for how cows are managed and milk is produced than is currently appreciated. Furthermore, it is likely that where grazing does feature, it is as a proxy for aspects relating to that class’s top preference, for example it is perceived to improve health and welfare or cow comfort, or make milk taste better.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank AHDB for its funding of this project, and for supervisors Jasmeet Kaler, Martin Green, Kate Millar and Jonathan Tan, all at University of Nottingham.

References

Cardoso, C.S., Hötzel, M.J., Weary, D.M., Robbins, J.A. and von Keyserlingk, M.A.G. (2016) Imagining the ideal dairy farm. J. Dairy Sci. 99, 1663–1671.

March, M.D., Haskell, M.J., Chagunda, M.G.G., Langford, F.M. and Roberts, D.J. (2014) Current trends in British dairy management regimens. J. Dairy Sci. 97, 7985–7994.

Miele, M. (2010) Report concerning consumer perceptions and attitudes towards farm animal welfare: official experts’ report. EAWP (Task 1.3). Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden.

van den Pol-van Dasselaar, A., de Vliegher, A., Hennessy, D., Isselstein, J. and Peyraud, J. (2014) Future of grazing in the Netherlands and in Europe. In: Proceedings of the 3rd meeting of the EGF Working Group ‘Grazing’, Aberystwyth, UK, 13–14.